Table of Contents

This tutorial provides a complete, step-by-step derivation of the Lorentz force law starting from the Lagrangian. The tutorial includes the derivation of key vector identities and explicitly details each term involved in the process. The goal is to make the content understandable even for someone new to the subject.

Step 1: Define the Lagrangian

The Lagrangian ![]() is a function that describes the dynamics of a system. For a charged particle of mass

is a function that describes the dynamics of a system. For a charged particle of mass ![]() and charge

and charge ![]() moving in electromagnetic fields described by a vector potential

moving in electromagnetic fields described by a vector potential ![]() and a scalar potential

and a scalar potential ![]() , the Lagrangian

, the Lagrangian ![]() is defined as:

is defined as:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[L = \frac{1}{2}m\vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \vec{\dot{x}} + q\vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \vec{A} - q\phi\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e9396de65a98254e91385848e55648b1_l3.png)

Here, ![]() is the velocity of the particle, and the dot represents a time derivative.

is the velocity of the particle, and the dot represents a time derivative.

Step 2: Compute

To proceed, we need to find the partial derivative of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() . This derivative is obtained as follows:

. This derivative is obtained as follows:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \vec{\dot{x}}} = m\vec{\dot{x}} + q\vec{A}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-58d404ab61cd18605f83527d338390cd_l3.png)

Step 3: Derive the Vector Identity

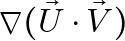

Before diving into the next steps, let’s derive a key vector identity that will be used later. The identity is:

![]()

The derivation of this identity involves using the definitions of gradient, divergence, and curl, along with the product rule for derivatives. Due to its complexity, it’s typically proven using tensor notation or by working through each Cartesian component.

Step 4: Compute  with Explicit Derivation of Terms

with Explicit Derivation of Terms

Now, we’ll find the partial derivative of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() . This involves differentiating the terms

. This involves differentiating the terms ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Derivation of the  Term

Term

The ![]() term differentiates to

term differentiates to ![]() when taking the gradient with respect to

when taking the gradient with respect to ![]() .

.

Derivation of the Last Two Terms from

Using the vector identity derived in Step 3, the gradient of ![]() becomes:

becomes:

![]()

These two terms will be part of ![]() .

.

Final Expression for

Combining these terms, we get:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \vec{x}} = -q \nabla \phi + q (\vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \nabla) \vec{A} + q \vec{\dot{x}} \times (\nabla \times \vec{A})\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-44bdbf54ec426d8247d930c329989931_l3.png)

Step 5: Euler-Lagrange Equation and Time Derivative

The Euler-Lagrange equation states:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial \vec{\dot{x}}} \right) - \frac{\partial L}{\partial \vec{x}} = 0\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-65f99217d2b0cf7ea83a39dab1aba883_l3.png)

To apply this equation, we need to find the time derivative of ![]() , which is:

, which is:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d}{dt}(m\vec{\dot{x}} + q\vec{A}) = m\vec{\ddot{x}} + q\frac{d\vec{A}}{dt}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d82a9cfd955077ddff543c543fb2cd50_l3.png)

The total time derivative ![]() includes both explicit and implicit time dependencies:

includes both explicit and implicit time dependencies:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d\vec{A}}{dt} = \frac{\partial \vec{A}}{\partial t} + (\vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \nabla) \vec{A}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-47061b41ef4d1862490e3d7653b4e70b_l3.png)

Step 6: Substitute into Euler-Lagrange Equation and Simplify

Having all the necessary derivatives and expressions at hand, we can now substitute these into the Euler-Lagrange equation:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial \vec{\dot{x}}} \right) - \frac{\partial L}{\partial \vec{x}} = 0\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-65f99217d2b0cf7ea83a39dab1aba883_l3.png)

We had:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d}{dt}(m\vec{\dot{x}} + q\vec{A}) = m\vec{\ddot{x}} + q \left( \frac{\partial \vec{A}}{\partial t} + (\vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \nabla) \vec{A} \right)\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b157b19eb8dae7239f2b28a4961c4eb4_l3.png)

And:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \vec{x}} = -q \nabla \phi + q (\vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \nabla) \vec{A} + q \vec{\dot{x}} \times (\nabla \times \vec{A})\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-44bdbf54ec426d8247d930c329989931_l3.png)

Substituting these into the Euler-Lagrange equation, we get:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[m\vec{\ddot{x}} + q \left( \frac{\partial \vec{A}}{\partial t} + (\vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \nabla) \vec{A} \right) = q \left( -\nabla \phi + (\vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \nabla) \vec{A} + \vec{\dot{x}} \times (\nabla \times \vec{A}) \right)\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-4e5928da693190ae39b41e212cae78f0_l3.png)

Simplifying, we find:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[m\vec{\ddot{x}} = q \left( -\nabla \phi - \frac{\partial \vec{A}}{\partial t} \right) + q \vec{\dot{x}} \times (\nabla \times \vec{A})\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d489e2907686246bda8efcef65e5f991_l3.png)

Finally, using ![]() and

and ![]() , we arrive at the Lorentz force law:

, we arrive at the Lorentz force law:

![]()

Conclusion

This concludes the comprehensive tutorial on deriving the Lorentz force law from the Lagrangian. The tutorial aimed to be as detailed as possible, explicitly showing the derivation of each term and equation involved. I hope you find this tutorial complete and informative.

SI

Derivation Using Limits

The Definition of the Total Derivative

The total derivative ![]() of a vector field

of a vector field ![]() is defined by the limit:

is defined by the limit:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d\vec{A}}{dt} = \lim_{{\Delta t \to 0}} \frac{\vec{A}(t + \Delta t, \vec{x}(t + \Delta t)) - \vec{A}(t, \vec{x}(t))}{\Delta t}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ad6176c7ba7424c04ffd2d541c0e35c7_l3.png)

Breaking Down the Limit Expression

We can express ![]() using a Taylor series expansion around

using a Taylor series expansion around ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\vec{A}(t + \Delta t, \vec{x}(t + \Delta t)) \approx \vec{A}(t, \vec{x}(t)) + \Delta t \left( \frac{\partial \vec{A}}{\partial t} \right)_{\vec{x}(t)} + \Delta \vec{x} \cdot \left( \nabla \vec{A} \right)_{\vec{x}(t)}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-50dd44c1d36cb74d3fd647f02d683b07_l3.png)

where ![]() .

.

Factor Out

Now, we can substitute this expansion back into the limit expression for ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d\vec{A}}{dt} = \lim_{{\Delta t \to 0}} \frac{ \vec{A}(t, \vec{x}(t)) + \Delta t \left( \frac{\partial \vec{A}}{\partial t} \right)_{\vec{x}(t)} + \Delta \vec{x} \cdot \left( \nabla \vec{A} \right)_{\vec{x}(t)} - \vec{A}(t, \vec{x}(t))}{\Delta t}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-80729453a63cf369e8e4c5ed24cc5a00_l3.png)

Factoring out ![]() in the numerator, we get:

in the numerator, we get:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d\vec{A}}{dt} = \lim_{{\Delta t \to 0}} \left( \frac{\partial \vec{A}}{\partial t} \right)_{\vec{x}(t)} + \frac{\Delta \vec{x}}{\Delta t} \cdot \left( \nabla \vec{A} \right)_{\vec{x}(t)}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f6e5ae7a745cf1d79d273dab8e1919dc_l3.png)

Taking the Limit

As ![]() approaches zero,

approaches zero, ![]() approaches

approaches ![]() , the velocity of the particle. So, we have:

, the velocity of the particle. So, we have:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{d\vec{A}}{dt} = \left( \frac{\partial \vec{A}}{\partial t} \right) + \vec{\dot{x}} \cdot \nabla \vec{A}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7d141f62d0c2a417a6808d6dddf1c04b_l3.png)

This gives us the expression for the total time derivative ![]() , which includes both the explicit and implicit time dependencies.

, which includes both the explicit and implicit time dependencies.

Certainly, demonstrating the vector identity through a concrete 3D example can offer a tangible way to grasp its intricacies. The vector identity we’re interested in is:

![]()

For simplicity, let’s consider ![]() and

and ![]() as 3D vectors defined in Cartesian coordinates

as 3D vectors defined in Cartesian coordinates ![]() :

:

![]()

![]()

Tutorial: Verifying the Vector Identity in 3D

Step 1: Compute

The dot product ![]() is given by:

is given by:

![]()

Step 2: Compute

The gradient of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() is:

is:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\nabla (\vec{U} \cdot \vec{V}) = \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial}{\partial y}, \frac{\partial}{\partial z} \right) \cdot (U_x V_x + U_y V_y + U_z V_z)\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0a92e1ab8b7df5e78042fa904ecadca8_l3.png)

This results in a vector with components:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\left( \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(U_x V_x) + \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(U_y V_y) + \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(U_z V_z) \right) \hat{i} + \text{(similar terms for } \hat{j} \text{ and } \hat{k} \text{)}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-585e81a99cf5bda2db34a87b75fbe60e_l3.png)

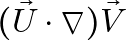

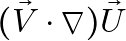

Step 3: Compute  and

and

The term ![]() can be written as:

can be written as:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[(U_x \frac{\partial}{\partial x} + U_y \frac{\partial}{\partial y} + U_z \frac{\partial}{\partial z}) \cdot (V_x \hat{i} + V_y \hat{j} + V_z \hat{k})\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e7cdf8c1d3ce6257313a4f7d5612ef9e_l3.png)

After performing the dot product, we get:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[U_x \frac{\partial V_x}{\partial x} \hat{i} + U_y \frac{\partial V_y}{\partial y} \hat{j} + U_z \frac{\partial V_z}{\partial z} \hat{k}\]](https://blog.lazying.art/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-6c246a0a4729c0476942911c98651b8d_l3.png)

A similar calculation can be done for ![]() .

.

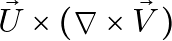

Step 4: Compute  and

and

Computing the curl ![]() and

and ![]() yields vectors in

yields vectors in ![]() components. The cross product

components. The cross product ![]()